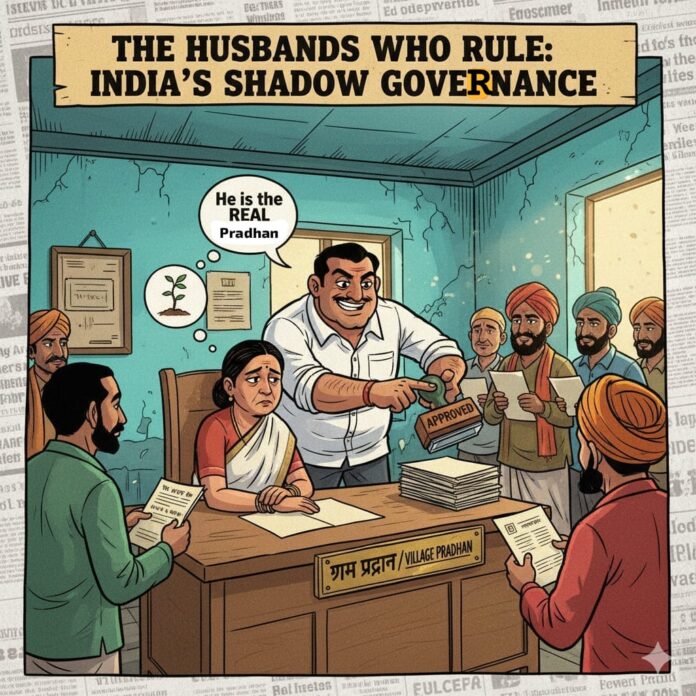

The Andaman and Nicobar Islands have long been projected as a region where grassroots democracy is alive and vibrant. But behind the numbers showing more women in elected office, a quieter reality is emerging: many women Pradhans and Councillors are being reduced to figureheads, while their husbands run the show from behind the scenes.

Reservation on paper

By law, one-third of all seats in panchayats and local bodies are reserved for women. The intent was clear, to break the stranglehold of male-dominated politics and create space for women’s voices in decision-making. Yet, as The Wave Andaman discovered, the policy’s promise is not translating into practice on the ground.

When this correspondent reached out to a woman councillor, a prominent woman councillor, and a sarpanch, the pattern was strikingly similar: it was their husbands who took the calls and confidently answered questions. In each case, the elected representatives remained silent, with their spouses asserting themselves as the actual decision-makers.

The phenomenon is widely referred to as “Pradhan-Pati” or “Sarpanch-Pati”, shorthand for the men who act as shadow leaders while their wives hold the official positions. While not unique to the islands, the practice here highlights how reservation is being hollowed out by entrenched patriarchy.

Observers say the issue is not just symbolic. When women are sidelined in this manner, governance itself is compromised. “This is not what the framers of the reservation policy envisaged,” said a political observer who has tracked local bodies in South Andaman. “The electorate voted for the women, not their husbands. When men step in, accountability gets blurred, and the very spirit of democracy is undermined.”

This shadow leadership also influences the way funds are allocated, how development projects are prioritized, and how disputes within villages are settled. In effect, the exercise of power remains with men, while the presence of women is reduced to satisfying the letter of the law.

Empowerment or tokenism?

The reservation of seats for women was meant to encourage leadership development, boost confidence, and give women direct exposure to governance. In many states, the move has produced inspiring stories of women sarpanches and councillors driving development agendas. But in the Andamans, as in many parts of India, the rise of proxy leadership risks turning the policy into tokenism.

“Numbers alone don’t equal empowerment,” said a former Zilla Parishad member. “Unless women are given both the space and the encouragement to exercise authority, they will remain sidelined. Right now, it is the husbands who run the show, and the women become rubber stamps.”

The issue is not openly discussed in political circles, partly because it is so normalized. But civil society activists warn that unless there is greater enforcement of accountability, for instance, requiring elected representatives themselves to attend meetings, answer official communications, and take part in decision-making, the practice will continue unchecked.

The stakes are high. With women’s representation enshrined in the Constitution and celebrated as a milestone in Indian democracy, the persistence of proxy leadership undermines both credibility and trust. It raises uncomfortable questions: is women’s political presence being used as a façade while power remains with men? And does this arrangement risk alienating women from politics altogether, discouraging them from seeing governance as their own domain?

So far, neither the administration nor the political establishment has taken strong steps to tackle the issue. For now, it is treated as an “open secret” that few want to confront directly.

The Wave Andaman has reached out to leaders of both the BJP and the Congress, as well as the Adhyaksh of the Zilla Parishad, South Andaman, seeking their views on the matter. Responses are awaited.