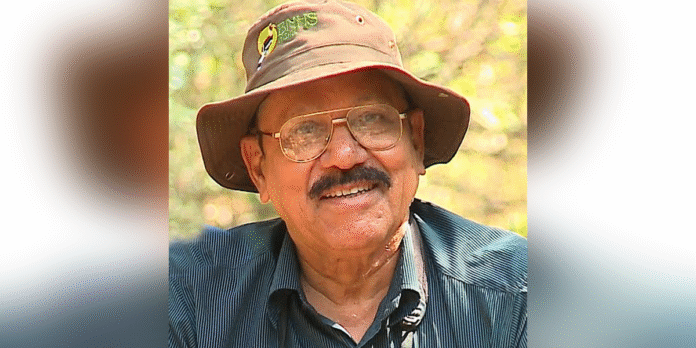

By Dr. Asad Rahmani

In the farthest reaches of India’s southern frontier lies an island cloaked in emerald mystery, Great Nicobar. Home to dense tropical rainforests, rare endemic species, and two indigenous communities, the Shompen and Nicobarese, it is a world where ecology and culture breathe as one. Yet, standing today at the edge of a sweeping transformation, this island has become the site of one of the most controversial “development” experiments in recent memory.

At the heart of this debate is a 130+ square kilometre mega-infrastructure project that includes a trans-shipment port, international airport, power plant, township, and luxury tourism zones. To its planners, the project symbolizes strategic progress. But to many ecologists, conservationists, and local residents, it marks the disintegration of a fragile and irreplaceable ecological soul.

Dr. Asad Rahmani, has been among those ringing the alarm bells. Dr. Rahmani is one of India’s most respected ornithologists and conservation scientists. He is the former Director of the Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS) and currently serves as Scientific Consultant to The Corbett Foundation and the Hem Chandra Mahindra Trust. With over 160 peer-reviewed scientific papers, 26 books, and decades of fieldwork across India’s most fragile ecosystems, including the Nicobar Islands – Dr. Rahmani has been a leading voice in ecological policy, habitat conservation, and public environmental education. His insights on the Great Nicobar project stem from deep, firsthand experience and scientific expertise.

His candid reflections on the project, based on decades of fieldwork across Nicobar and Tillangchong, serve as both a warning and a roadmap. His message is clear: “Conservation is not a barrier to progress. Conservation is progress.”

What Makes Great Nicobar Irreplaceable?

Great Nicobar is not just another island; it is India’s last remaining lowland tropical rainforest in its purest form. It is home to unique species like the Nicobar megapode, an endemic bird that buries its eggs in warm coastal sands, and endangered reptiles, amphibians, and insects that exist nowhere else.

But it is not only biodiversity that is at stake. “The island is also home to a delicate forest-hydrology dynamic,” says Dr. Rahmani. These ecosystems regulate monsoon drainage, recharge aquifers, and provide a natural infrastructure that no amount of cement can replicate.

Tillangchong, another nearby island he has visited, stands as an example of coexistence, where traditional practices like seasonal coconut harvesting and wild boar hunting by the Nicobarese leave minimal impact on the land. “There are traditions that have lasted for hundreds of years with little harm. The same cannot be said of recent interventions,” he notes.

The Illusion of Due Diligence

Development, especially on this scale, demands rigorous environmental scrutiny. India’s Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) framework is supposed to serve that purpose. But as Rahmani starkly puts it, “EIA reports are a big sham, tailored to validate decisions already made.”

When an EIA fails to acknowledge or meaningfully respond to obvious risks, like habitat fragmentation, species migration disruption, or hydrological imbalance, it ceases to be a safeguard and becomes a rubber stamp. In the case of Great Nicobar, the EIA and its resulting clearances have been widely criticized for their superficial treatment of ecological costs and for ignoring the concerns of local and tribal communities.

Even well-known ecological principles, like the need for wildlife corridors, which are now implemented in tiger reserves, are often missing in island ecosystems where the need is equally urgent.

Invisible Impacts, Irreversible Damage

One of the most overlooked consequences of projects like this is habitat fragmentation. Dr. Rahmani warns that we may be on the brink of losing the Nicobar Megapode, a ground-nesting bird uniquely adapted to coastal forest ecosystems. With “vikas” arriving at the shoreline, the very land where it breeds is set to be reclaimed or repurposed.

And then there are the invisible impacts, on hydrology, subsoil moisture, microclimates, and food webs. Wetlands that once flourished naturally are now often cemented under schemes like the Amrit Sarovar project in the name of beautification, cutting off their water sources. “Soon these wetlands dry or shift their character. Millions are then spent artificially pumping water back in,” says Rahmani. A tragic irony.

An Ecological Tipping Point?

What is unfolding in Great Nicobar is not isolated, it mirrors a broader national trend where ecology is traded for optics of economic growth. In theory, India has committed to protecting 30% of its land and marine ecosystems under the global 30×30 pledge. Yet here we are, clearing 178 sq. km of rainforest on a single island.

Rahmani believes we’re approaching an ecological tipping point, one where species will not just decline but vanish. “The loss of even one species, especially an endemic one, is irreversible,” he warns. Once gone, they take with them millions of years of evolutionary history and irreplaceable ecological services.

Is There Another Way?

The answer, Rahmani insists, is yes. But only if we redefine development itself.

“Strict protection and keeping natural integrity is also ‘vikas’,” he says. In fact, he argues, the best kind of development is one that elevates both human wellbeing and ecological resilience. India can pursue infrastructure, technology, education, and industrialization, without plundering its last remaining wild spaces.

The key lies in meaningfully integrating ecological science into policy, and ensuring genuine community consultation. That starts by respecting existing laws and governance systems, which are already being circumvented in this case. “Even the agencies meant to protect the tribal people have signed away their land,” he laments.

A Message to the Youth of the Islands

To young planners, students, and citizens in the Andamans and Nicobars, many of whom dream of better roads, connectivity, and opportunities, Rahmani offers a message of balance: “Nature itself is infrastructure. Destroying it for temporary gain is no gain at all.”

He urges islanders to push for an alternative model, one that invests in human development without undermining the ecological fabric that supports it. “If we think of progress only in terms of concrete and glass, we will soon find ourselves standing on a hollow foundation.”

The Path Forward

The debate over Great Nicobar is not just about an island, it is about what kind of development India chooses to pursue in the 21st century. It is about whether we see forests as mere land banks for construction, or as life systems that nurture water, weather, and food security.

It is about whether we value the wisdom of indigenous people and field ecologists or continue to ignore them until it’s too late.

It is about whether we can look back, decades from now, and say that we chose restraint over recklessness, regeneration over ruin.

Great Nicobar doesn’t need to be sacrificed. It needs to be respected. That is the real progress.