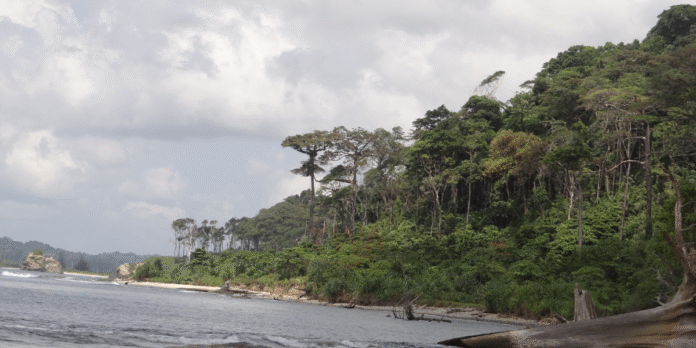

At the southern edge of India, closer to Sumatra than to the mainland, lies Great Nicobar, a remote island thick with forests, ringed by coral reefs, and home to some of the most vulnerable communities in the country. Today, this outpost of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands has become the stage for one of India’s biggest development gambles in decades.

The project in focus

The Union government’s “holistic” plan for Great Nicobar promises transformation on a scale the island has never seen. Anchored around four pillars, a massive transshipment port at Galathea Bay, a new international airport, a 450 MVA power plant, and a modern township, the project carries a price tag of over ₹80,000 crore.

Officials argue the location is unbeatable: barely 90 nautical miles from the Malacca Strait, a chokepoint for global shipping. A deep-water Indian hub here, they say, will reduce dependence on Colombo and Singapore, cut logistics costs, and secure India’s maritime future. Last year, the Centre went a step further, notifying Galathea Bay as a “major port,” giving Delhi direct control over its development.

The ecological flashpoint

But the blueprint comes at a cost. More than 130 square kilometres of pristine forest are set to be diverted, with phased felling of over a million trees. Critics argue that compensatory plantations in Haryana cannot replace old-growth tropical forests. Scientists warn of disruption to nesting beaches of the leatherback turtle, coral habitats, and the delicate island ecosystem.

For the Shompen, a Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group with little contact with the outside world, the stakes are existential. Anthropologists caution that the arrival of thousands of migrant workers could bring diseases and social upheaval that the community may not survive.

Sonia Gandhi’s sharp words

Congress Parliamentary Party chairperson Sonia Gandhi has seized on these concerns. In a signed article this month, she called the project a “grave misadventure” that tramples constitutional safeguards for indigenous people and ignores the ecological fragility of the islands. Gandhi accused the government of bulldozing due process, warning that both the Nicobarese and Shompen face cultural erasure if the plan goes ahead unchecked.

Her words, amplified by party leaders, have put the government on the defensive and ensured the project remains under political scrutiny.

The government’s defence

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has left no doubt about his support. Calling it a project “of strategic, defence and national importance,” he argued that “economy and ecology complement each other.” The government insists safeguards are built into the plan, including “green development zones” where no trees will be cut, staged clearances, and conservation offsets.

Officials stress that India cannot afford to miss the opportunity to create a world-class port at its maritime frontier. The long build-out, they add, will allow impacts to be managed over time.

The commercial push

Beyond strategy and politics, the Great Nicobar Project is also a magnet for business. Several leading Indian infrastructure conglomerates and foreign construction majors have already expressed preliminary interest in bidding for various components, from port construction and dredging to airport development and township building. Their involvement underscores the commercial stakes: whoever secures contracts here will be part of one of India’s most high-profile infrastructure ventures of the decade.

The development dilemma

If completed, the Great Nicobar Project could redraw India’s logistics map and change life on the islands. The airport and township promise jobs, connectivity, and investment. Strategically, the project reinforces India’s military posture at the gateway to the Pacific.

Yet questions remain. Can the islands’ fragile carrying capacity withstand a surge of new settlers and infrastructure? Will ecological safeguards hold in the face of dredging, breakwaters, and urban sprawl? And most importantly, can India balance strategic ambition with its constitutional duty to protect its most vulnerable citizens?

What lies ahead

With major-port status already secured and preparatory work under way, the project is moving forward. But legal challenges continue before tribunals and courts, and activists are pushing for a full independent review.

The debate now sits at the heart of India’s development story: whether a bold plan on a remote island can deliver prosperity without becoming an ecological and human tragedy. The answer may decide not only the future of Great Nicobar, but also how India defines development in its most fragile frontiers.