As Sri Vijaya Puram prepares to welcome Union Home Minister Amit Shah and RSS Sarsanghchalak Mohan Bhagwat, the national gaze once again shifts to Vinayak Damodar Savarkar and the haunting walls of Cellular Jail. It is fitting that Savarkar is remembered here. These islands shaped him, scarred him and strengthened him. His decade-long imprisonment, marked by torture, isolation and relentless mental assault, stands as one of the defining chapters of India’s freedom struggle.

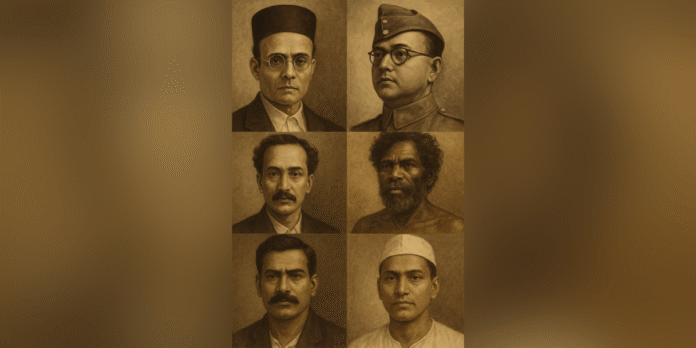

But even as Savarkar’s legacy is honoured, the islands are confronted with a troubling truth: India continues to forget the hundreds of other martyrs who suffered in these same cells, on these same docks, under the same chains.

A walk along the top floor of the Cellular Jail, where memorial plaques bear the names of political prisoners transported from every corner of the subcontinent, reveals the sheer scale of this historical neglect. These plaques are not mere inscriptions; they are reminders of lives destroyed, of men who were starved, whipped, shackled and broken in the service of an empire’s cruelty. Ullaskar Dutta, for instance, was chained for life and subjected to daily brutality. His suffering was no less than Savarkar’s, yet his story barely receives a whisper in national memory.

And Ullaskar Dutta is not alone. Punjab’s revolutionaries, Bengal’s militants, Burma’s rebels and patriots from the Deccan and the North-East all shared this island of punishment. Many never left. Many were buried without ceremony or record. India’s textbooks do not name them. India’s leaders do not visit their plaques. India’s memory betrays them.

Equally ignored is the monumental contribution of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose. It was Bose who ensured that Andaman and Nicobar became the first liberated territory of modern India in 1943, an act unparalleled in symbolic power. Yet beyond the naming of Netaji Stadium, there has been no sustained effort to integrate Bose’s extraordinary Andaman chapter into national consciousness. A land that hosted the Azad Hind Government ought to stand at the centre of India’s independence narrative, not on its periphery.

The neglect is even more pronounced when it comes to the indigenous communities whose histories predate the Cellular Jail. The Great Andamanese tribes fought with unmatched courage during the Battle of Aberdeen in 1859, resisting colonial encroachment at a time when organised tribal resistance was nearly impossible. The casualties they suffered were catastrophic; their population, culture and homeland were devastated. Yet this defining moment receives little attention beyond scattered footnotes. The names of their leaders, their sacrifices and their defiance remain unrecognised in the national imagination.

All of this underscores a painful reality: Andaman’s role in India’s freedom struggle has been reduced to a single narrative. Savarkar is a towering figure, and his remembrance is justified. But to centre him alone while neglecting the hundreds who endured the same chains distorts history and diminishes the islands’ true legacy.

This is why today’s commemorations must serve not only as a tribute but also as a reckoning. The Union Government owes the islands a more honest engagement with their past. It owes the forgotten martyrs of these waters and forests the dignity of remembrance. It owes Netaji’s legacy a place of prominence. It owes the tribal communities the acknowledgment they have long been denied.

The Wave Andaman believes that the story of these islands is not one man’s story. It is a story of hundreds, freedom fighters, revolutionaries, tribals and patriots, whose courage shaped India but whose names fade deeper into silence each year.

Honouring Savarkar is right. Forgetting the rest is not.