The recent decision by the Central Board of Secondary Education to mandate the appointment of dedicated career counsellors in affiliated schools has been widely seen as a long-overdue acknowledgment of students’ academic and career-related needs. However, education experts caution that the success of the directive will depend largely on how India addresses gaps in professional training, regulation and quality assurance in the field of career guidance.

For nearly a century, Indian education policy has consistently recognised the importance of guidance and counselling in schools. From early policy deliberations in the pre-Independence period to the National Education Policy of 2020, official documents have emphasised the need for structured support to help students navigate education, personal development and career decisions. Despite this consensus, career guidance has remained marginal in practice, often bundled into general counselling roles, handled informally by teachers or outsourced to an unregulated private sector.

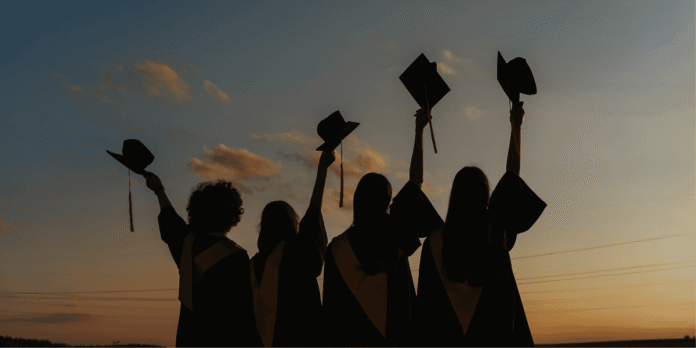

The latest amendment to CBSE’s Affiliation Bye Laws marks a departure from this approach. By requiring schools to appoint a career counsellor as a role distinct from the counselling and wellness teacher, the Board has formally recognised career guidance as a specialised function. This shift comes amid growing concerns over academic stress, student mental health and uncertainty around post-school pathways.

Until now, CBSE norms required schools to appoint a counselling and wellness teacher, operating on the assumption that socio-emotional support could adequately address academic and career-related concerns. The revised provision acknowledges that career guidance demands a different skill set, including career assessment, labour market awareness, understanding of higher education options and engagement with parents, universities and industry.

The timing of the directive is also significant. In 2025, the Supreme Court of India delivered two judgments underscoring the importance of mental health in educational settings, including a set of guidelines that explicitly linked career uncertainty with academic stress and psychological vulnerability. In this context, CBSE’s move aligns both with national education policy priorities and judicial observations.

At the same time, the notification implicitly highlights a structural constraint: the shortage of trained career counsellors in the country. CBSE has allowed schools to appoint trained teachers in the interim, granting them a two-year window to acquire the required qualifications. While pragmatic, this provision also exposes systemic weaknesses in professional capacity.

Career guidance in India continues to be dominated by practitioners without formal training in career development. Teachers, social workers, human resource professionals and private entrepreneurs account for much of the current workforce. Dedicated academic pathways remain scarce. India reportedly has only one postgraduate programme focused exclusively on career guidance, with limited diploma and certificate options. Even in broader guidance and counselling programmes, career development is often restricted to a single module.

The National Council of Educational Research and Training’s International Diploma in Guidance and Counselling is among the few structured initiatives in this space, though career development forms only a small part of its curriculum. Given the scale of India’s school system, experts argue that existing training mechanisms fall far short of demand.

CBSE’s directive outlines minimum educational qualifications and proposes 50 hours of preferred capacity-building programmes, but several operational questions remain unanswered. These include who will design and deliver the training, how quality will be assessed, how skills will be certified and updated, and what ethical standards will govern professional practice.

At present, career guidance in India lacks a unified competency framework, accreditation mechanism or enforceable code of conduct. While professional associations play a role in advocacy and networking, their regulatory reach is limited. Without a robust quality assurance system, there is concern that schools may treat the mandate as a compliance exercise rather than a substantive support mechanism for students.

In practice, especially in resource-constrained regions, teachers are expected to continue carrying a significant share of career guidance responsibilities. Educationists argue that this reality must be acknowledged through mandatory career guidance components in teacher education programmes and structured, practice-oriented training.

Experts also point to alternative delivery models, such as school clusters or hub-and-spoke systems, where trained professionals support multiple schools. Clear boundaries, they stress, are essential, with complex or psychologically sensitive cases handled only by qualified professionals.

The CBSE directive, educationists note, is not a final solution but an important starting point. Its long-term impact will depend on whether India invests in strengthening academic programmes, establishing national standards and building an ethical, professional ecosystem capable of supporting students through increasingly complex career decisions.