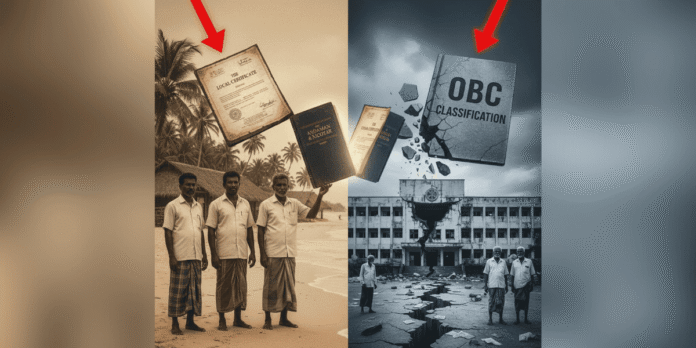

In an incisive commentary titled “Two Policy Choices That Bent the Arc of Island Politics,” writer and policy observer Sanjay Balan revisits two administrative decisions of the 2000s that, he argues, quietly transformed the social and political landscape of the Andaman & Nicobar Islands. These were the replacement of the Local Certificate (LC) framework with an Other Backward Classes (OBC) classification, and the creation of a separate North & Middle Andaman district in 2006. While both moves were presented as practical governance measures, Balan contends that their long-term costs have outweighed the short-term convenience they offered.

The first shift, replacing the LC system with OBC categorisation, marked a major departure from the islands’ social evolution. The LC framework, he recalls, reflected the territory’s unique demographic story: one shaped by settlers, freedom fighters, ex-convicts, and displaced families who had together built a cohesive and largely class-light society. The LC served as a domicile-based protection that ensured educational opportunities for residents without importing mainland caste structures. When courts questioned LC’s lack of legal standing, the more appropriate step, Balan argues, would have been to give it statutory backing through a domicile law.

Instead, the administration adopted the OBC model, designed for deeply stratified mainland societies. Over time, this imported framework, he notes, encouraged competing claims to “backward” status and eroded the shared islander identity the LC had protected. He suggests that the better path would have been to legally codify domicile, retain higher-education reservations, and address job scarcity through constitutionally sound local-preference policies suited to island conditions.

The second turning point came in 2006, when the North & Middle Andaman district was carved out of the original Andaman district. The move was justified on geographic and administrative grounds, remoteness and governance accessibility, but Balan notes that the population base was too small to warrant a full-fledged parallel administration. With improvements in the Andaman Trunk Road, ferry links, and online service delivery, the core argument for bifurcation, he says, has steadily weakened.

The duplication of district establishments has also had fiscal implications. Running two administrative setups, he points out, means diverting limited funds away from critical development priorities such as health, education, and livelihoods. On the political front, the split diluted the voice of islanders by fragmenting the previously strong Zilla Parishad structure, shrinking the platform for territory-wide deliberation and leaving a “political vacuum that everybody senses and nobody benefits from.”

Balan identifies a common flaw in both policy choices, importing mainland templates without adapting them to island realities. What the LC needed, he says, was a law, not a label; what decentralisation required was empowered local democracy, not duplicated bureaucracy. The cumulative result, he argues, has been slower, more expensive development and a diminished public sphere.

He proposes a three-part corrective: enact a domicile law to restore the Local Certificate system with legal backing, conduct a cost-benefit review of the 2006 bifurcation to determine its relevance, and re-empower the Zilla Parishad with genuine financial and functional autonomy.

“For decades, the islands quietly achieved what many societies aspire to, a cohesive, upward-moving community built on shared effort rather than inherited privilege,” Balan concludes. “Our task now is not to chase other people’s templates but to legally restore our own.”